Enunciation (this is for Musicians)

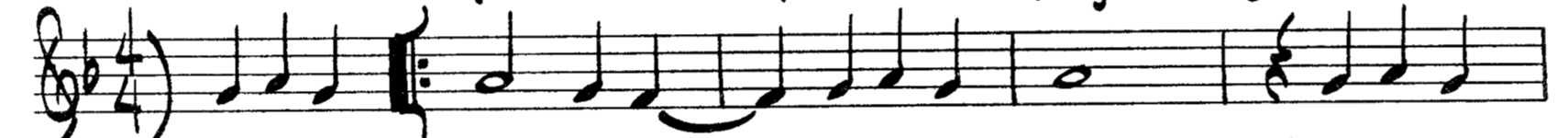

“They’re writing songs of love, But not for me”. Sing this first line of the Gershwin tune — or just say it. (In the above, the rhythms are all wrong — nobody sings it that way!) Sing it lyrically: Listen to yourself again, and notice where the loud notes are. I think most people innately do it like this:

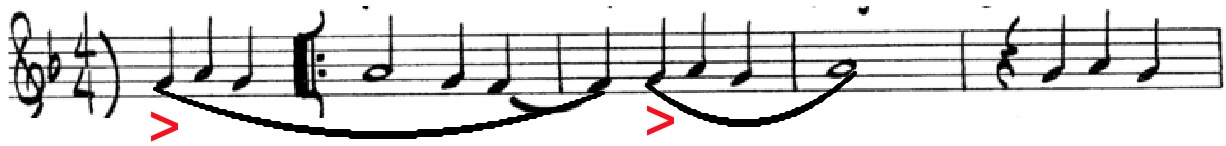

An accent isn’t exactly the right notation. But there is a feeling of a start, a definiteness on that first note. Listen to Ella Fitzgerald, Judy Garland, Doris Day, etc.

Popular music loves off-the-beat notes — the “and”’s, syncopations, back-beats, etc. Similarly, lyrical phrasing like the above seems to be more intrigued with the journey to the downbeat than the downbeat itself. Classical musicians can learn a lot from this.

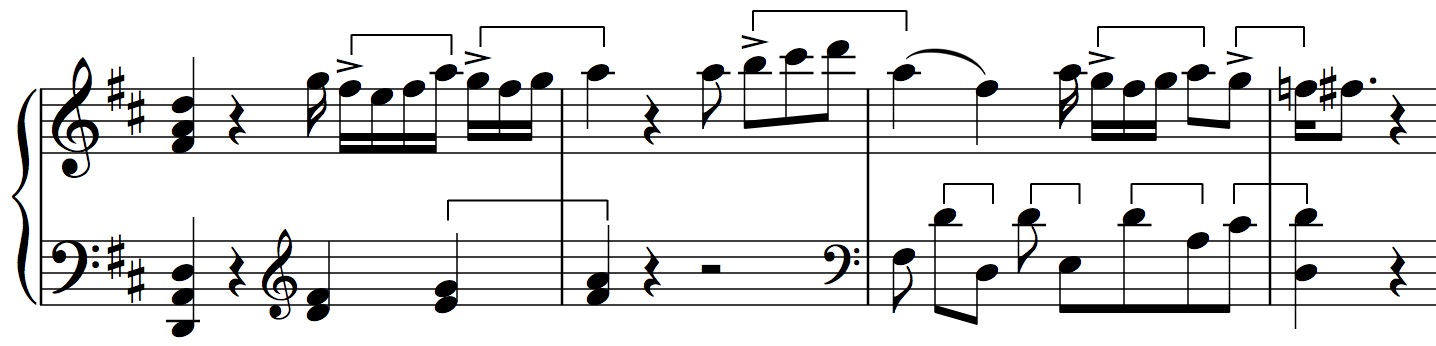

Try applying the above to this Mozart Sonata (K. 576):

Try putting that same feeling of “start”/impetus/energy on the first note, and keep that energy all the way to the top (the end of the bracket.) You might think you need to give little accents on the notes that fall on the beat, otherwise people will be confused where the beat is. But they don’t need it, and it actually makes it sound flat-footed.

Now a little further out, play this Mozart Sonata (K. 311) like this:

Notes:

- The brackets tell you how to group the notes in your head.

- The faster you go, the more you need to work to show where the groups start — thus the accents.

- BUT… the accent doesn’t mean NOT to accent the other 3 notes! In fact, think: follow-through. Make sure the remaining 3 notes of the group maintain the energy, clarity and definiteness of the first note.

Play the music this way in tempo, and suddenly you’ll sound like a pro. Every note will be heard in the last row of the concert hall, every note goes somewhere.

Quite a revelation to classical musicians who through years of training are continually told that the notes ON the beats are the important ones. Everything about notation gives that impression. Metronome practice give that impression. Chord changes are almost always ON the beat. Even the music itself, where big moments are almost always on a downbeat — all of this pulls us away from (what I think is) proper enunciation,

There are all kinds of implications of this approach. I could demonstrate what I consider proper playing of running 16ths (4 notes per beat) and triplets. Building technique is as much about training our ears to hear quickly. But for pianists, I recommend a “hitty” rather than “pressy” approach to the keys to create this enunciation.

I have to credit the conductor Mitch Miller for pointing me in this direction. Some older readers may remember him — he had a TV show called “Sing Along With Mitch.” He was an insightful musician (oboist and orchestra conductor) who was also the A&R man for Columbia Records (signed such people as Johnny Cash, Frank Sinatra, Erroll Garner) and was attuned to the common traits of great music-making of all genres. He was a huge fan of Pablo Casals and Murray Perahia.

What I like about this topic is that it is concrete, applies to all instruments and can improve every measure of every style of music that you play.

Concert Highlights

-

17 januaryFort Myers, FL

-

25 januaryPalm City, FL

-

27 januaryMarathon, FL

-

28 januaryTavernier, FL

-

16 februaryWestport, MA

Website Provided by NIKKIVA